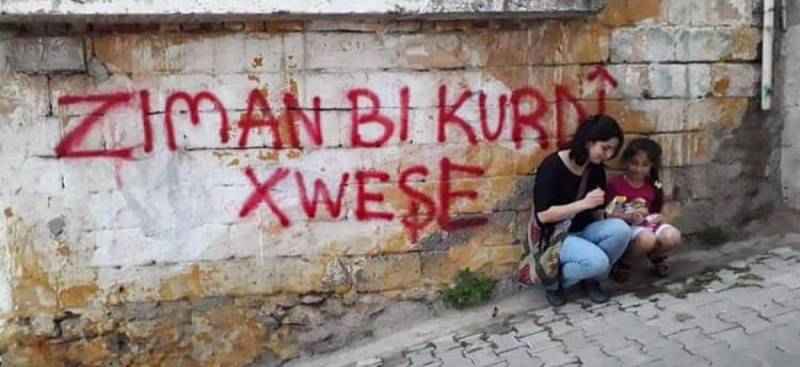

Last week, while strolling through the streets of Sur, I came across a group of girls and started a conversation with them. Can they attend online classes, do they have tablets or phones, how are their days during the pandemic… As I talked to them, I realised the reason why the girls looked at me with admiration:

– Sister, how well do you speak?

– How so?

– Your Turkish is very nice.

– Is that so? You speak well, too.

– No, I can’t speak well like you. I mean, because of my Kurdish.

– Kurdish is your mother tongue and you speak it very well. Kurdish is also my native language, but look, I cannot speak Kurdish well either. I have been taking lessons to speak Kurdish for years.

– I don’t want to speak Kurdish though.

– Why is that?

– Kurdish is not good.

– Why is Kurdish not good?

– I mean, if it is beautiful, wouldn’t it be at school?

– Kurdish should of course be spoken at school and everywhere, but its non-existence does not mean that Kurdish is not beautiful …

– No, I still want to speak Turkish well. Turkish is better.

These words made my heart hurt that day. Of course, my new friend, Berivan, is not the only child to think like that. Research conducted by Handan Çağlayan in 2014 – later published in a book entitled “Different Languages in the Same House” – revealed the language perception of Kurdish children in a very striking way. The issue of how Kurdish is transmitted through generations, or not, and the answers given by Kurdish children to Handan Çağlayan’s study, which examined the reasons in terms of rural / urban, gender, immigration and class positions, are very striking:

– Are Turkish speakers poorer or Kurdish speakers?

Kurdish speakers are poorer.

– How do Turkish speakers dress?

– They dress well. Their hair is combed properly.

– They wear jeans, shirts or something. Their clothes are beautiful.

– How do Kurdish speakers dress?

– They wear long skirts. They wear their hair in a bun.

– They wear headscarves. Their hair is messy.

– English speakers?

– They are beautiful.

The pressure on Kurdish was dialed down in the mid-2000s thanks to the peace process and the electoral success of the Kurdish political movement in local municipalities. Kurds enjoyed using Kurdish in public and private spaces, local administrations, conferences, meetings and in universities and television broadcasts. Still, the change in Kurdish children’s own perception of language was very limited due to the hierarchy between languages.

Maybe if the peace process continued, things could start to change for Kurdish children. However, the end of the peace process, the armed clashes in the provinces of the region, the increasing pressure on Kurdish have halted the positive process, and the use of Kurdish has been diminished again.

In the last five years, Kurdish-language schools were closed, newspapers and magazines published in Kurdish were shut down. Kurdish-teaching kindergartens and philological institutes at universities were abandoned. We’ve moved 80 years backwards in terms of language freedom, back to the 1940s. In the last 5 years, Kurdish has sometimes been recorded as an “unknown language”.

In June 2020, at a hearing of the trial of journalist Ferda Yılmazoğlu and Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) women’s council member Seyhan Çiçek, the prosecutor rejected identifications in Kurdish, saying it is “an incomprehensible language”. Thus, the Turkish authorities considered Kurdish an “incomprehensible language”.

Of course, an “incomprehensible language” has no value in shaping public policies and services. The Turkish Ministry of Health releases leaflets in 6 languages which include French, Arabic, English, Russian, German and Persian in defiance of the Kurdish citizens, who make up at least a quarter of the country.

Feb. 21 marked International Mother Language Day. Yet in my country, the land where I was born and grew up, my language is somehow “incomprehensible”. My generation grew up with a “language agony”. We did not understand our grandfathers, grandmothers, and sometimes even our parents. We were left incompetent, left without roots. We were deemed “mentally retarded” because we did not understand the language in schools. We were told that our language was worthless and thus we were ashamed of our own language and the world surrounding it.

However, as children of an “incomprehensible language”, we have not been assimilated and given up our identity despite all the pressures. The crackdown on our language did not cause us to love this country more. Hatred towards Kurdish has not made this country a better, prosperous country. Berivan will also pass through the roads most of us passed in the 80s and 90s.

The day will come when she will understand what was done to her, how she was removed from her roots. Even if she forgets her mother language when she grows up, she will struggle to keep other children from being disenchanted with Kurdish. She will stick to that until the “incomprehensible language” becomes comprehensible until the language, culture and identity of the children of the “incomprehensible language” are respected in this country.