“It must be nice to able to wear a shirt.’’

The remark above was uttered by a child I met last year, who was crippled by a landmine explosion in the majority Kurdish southeast of Turkey.

The story of this boy, who I will call Hasan, echoes that of hundreds of children in the region, whose bodies have been riddled with shrapnel due to the existence of some 400,000 landmines laid in the region in the 1990s, at the height of a conflict between the Turkish security forces and Kurdish militants.

Children in the region generally reach for what they think is a toy as they are grazing animals, out playing with their friends or en route to school. Then there is a horrifying explosion followed by a deep, dark abyss.

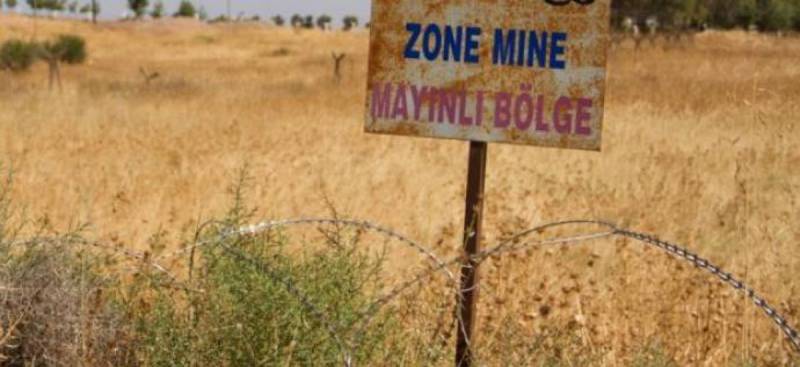

Turkey’s landmines and unexploded munitions are at a critical level. The country is reported to have around one million land mines. And there are another three million kept in storage and in need of destruction. These mines are not just located along the country’s borders, but also extend well into Turkey.

In the 1990s, landmines were often laid around police stations and evacuated villages. Today nobody knows where they are. Officials released a statement in 2004 saying that Turkey’s landmine map had been lost. Remarks by a certain former chief of staff suggest that Turkey never had a proper map to begin with.

Turkey signed the Ottawa Convention, also known as the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty, in 2003. It calls for the removal of mines and the protection of civilians. Accordingly, Turkey had until 2008 to get rid of all the mines in its stock and clean up all those laid by 2014. It failed to fulfil this responsibility and asked for another 10 years. The United Nations gave Turkey an additional eight years instead. In short, the country has until 2022 to get rid of all its mines. This goal appears virtually impossible to achieve.

There have been a few positive developments. In 2015, Turkey founded the Turkish Mine Action Centre (MAFAM) under the auspices of the Defence Ministry. It began working to remove landmines immediately after it was established. Moreover, with funding received from the European Union and in cooperation with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), a new project was launched to rid the country’s eastern borders of the ordnance.

Landmine removal started, beginning with Turkey’s eastern borders. I can say that this project was among the most valuable of all those carried out with EU funding with the UNDP, because the initiative is saving lives. Each mine removed means potentially saving a child or a refugee looking to cross the border or any person it may have affected. As such, it is very valuable.

Returning to the victims of landmines…

People were able to receive some help after a change in Turkey’s Social Security Institution (SGK) laws in 2012, which helped them obtain artificial limbs and medical treatment. Medical teams travelled to the country’s most remote locations, bringing with them prostheses. For those who had lost their limbs or eyes in explosions, officials reaching out to them for aid was incredibly important.

However, about three years ago, the government cut support for medics working on this initiative and subsequently many medical companies went south. Then inflation rates soared, along with the price of prostheses.

In the end, the region’s landmine victims were abandoned to their own fate. It now appears very difficult for them to obtain artificial limbs. The aid given by the SGK accounts for one third of the cost of artificial limbs and children who are growing are in constant need of new ones.

A good Samaritan came to the aid of Hasan and he now has arms and can wear shirts. But what about all the other children we cannot reach? What will happen to them?

We just celebrated International Land Mine Awareness Day on April 4. But, unfortunately in Turkey, there is not effort to mark this occasion by public institutions or civil society.

There are Hasans playing in fields in the east of the country, dangerously close to landmines. And we are far away from protecting them.